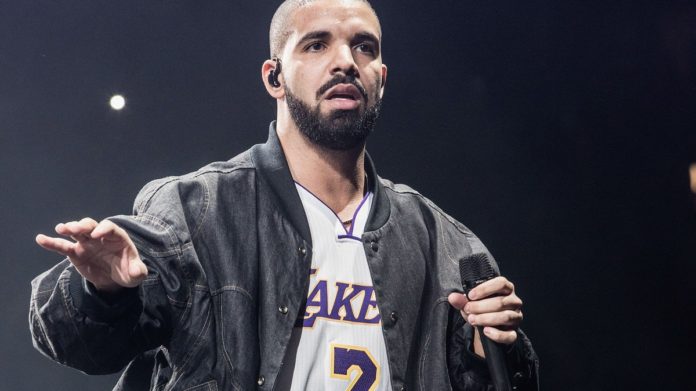

Drake has been safe for a long time. Throughout his career he’s consciously built himself one of the biggest parachutes the rap world has ever seen. He’s proven himself one of pop culture’s greatest glad-handers, ingratiating himself to the general public by embracing pop as his vernacular, borrowing from the many musical traditions of the global black diaspora, and generally folding even the parts of his personality that aren’t quite as cool into his overall persona. It’s the main reason why in every public spat he’s had before this year, he’s never come out with scars. Even after the shellacking that Pusha T gave him a month ago with “The Story of Adidon,” there’s still no real way for Drake to fail. He’s shored himself up enough at this point that, commercially, he’s likely going to be at the top of the food chain until he feels like scaling it back or calling it quits.

Though he’s commercially transcended hip-hop, any halfway follower of his career would know that he’s been jostling for respect in a genre that by many accounts, left very little wiggle room for someone like him – non-American, perceived as privileged, painfully corny at times – to not only get in, but to thrive against the odds. But Pusha T, an artist from the school of nothing-is-off-limits rap beef, saw room to change the narrative and on his response to Drake’s “Duppy Freestyle,” he revealed Drake had fathered a son with former adult film actor, and kept him from the public eye. According to Push, not only was Drake a father, he was an absentee father. With the diss, lines like Drake’s “I could never have a kid and be out here still kiddin’ ‘round” from More Life’s “Portland” started to take on a different meaning and appear hypocritical.

In the month since, fans have waited for a Drake response, which was supposedly barred from being released by early supporter and mentor J Prince. But on his latest album Scorpion, instead of continuing to fight with Push, Drake has been forced to talk about a new part of his life that looks to be the source of significant discomfort, embarrassment, and hurt.

Drake mentions his son and reasons for not revealing him a few times on both Side A and Side B of the excessively long album – but most of the references to his child come in the form of corny punchlines that feel emotionally distant. On “8 Out of 10” he urges: “The only deadbeats is whatever beats I been rapping to.” On “Emotionless,” one of the album’s standouts, he insists, “I wasn’t hiding my kid from the world, I was hiding the world from my kid,” mentioning that he wanted to shield himself from the comments people might have about his son on social media. It’s fair. But it’s hard to read his intent. On one hand, not a whole lot is known about Drake’s personal life outside of gossip and his carefully curated online persona. His posts on social media are less about his intimate life as much as they are about promotion. On the other, he’s talked about being at odds with his own father, aired out government names of past flings, and opened up about not…