Janice Speights, 81, is walking down the corridor, her Afro-patterned dress swishing rhythmically as she kept a steady stride. “I’m a walker,” she says into the air. She places her frail, yet deliberate hand on the shoulders of almost everyone she passes. Some with walkers, some accompanied by a care provider of some kind. She needs no assistance. In her 81 years, she still prefers to take the stairs.

Speights has been living at Sedgwick Heights Loretto assisted-living facility for seven years, and in that time has met a number of friends and acquaintances— both new and old.

Ninety-year-old Julie Ringham is one of them, an old friend for that matter—and a former governmental secretary who worked at The Times Building downtown Syracuse, not especially far from where Speights used to work, some 50-odd years ago they concurred with laughter. Their friendship was unconventional in its heyday—Ringham being from white suburbia, and Speights from a small town in Alabama. Somehow, despite deep racial tensions that overcame the city well into the 1960s, the women managed to become good friends.

“I love her. She’s like a sister to me, more than a sister. It’s who she is that makes her so special,” Ringham said. “It’s that strong personality,” she says with a laugh. Speights smiled adoringly, gave her a hug, and gently moved passed her down the hallway.

Finally, she arrives to her apartment on the third floor. The door swings open, and she walks in first, with her hands opened beside her. The first thing that can be seen is a row of potted plants, lining a wide window. She swivels and says “so this is where I live.” Her face bares a matter-of-fact- grin. “Now you know everything about me,” she muses.

She makes it a point to acknowledge the lack of family photos—her most treasured artifacts— most of which were still in storage.

“I also love flowers,” she says, as she makes a sharp advance to her plotted plants, queuing herself into details as to how she got them. “And this one was from Mother’s Day last year,” she said, fingering the leaves of a large leafy plant that she admitted to not knowing, or caring for its technical name. All that mattered that it was gifted to her from her six, now-adult children.

She is exhausted, this I can tell, after a long morning of ceaseless conversation.

“But let me tell you before I forget,” she said. “The most important thing that I ever done, was teach my children that they had value. That everyone had value,” she said, “That you also treat yourself with humility,” she added, before she was reminded of other life-lessons in which she imparted on me wholly before escorting me out.

Hours before, Speights had been enjoying a concert in the common room. The musical performance of the afternoon had just left, leaving Speights to do what she does best. Socialize.

Speights was seated at a table among four people. She was partaking in a rather heated discussion, as to ‘whom was the better James Bond.’

As the first African-American teller at Lincoln Bank on 112 South Salina St, Speights had acquired an unmistakable gift for pleasantry—and was able to entertain a conversation of any genre. Her hand was propped beneath her chin, as she placed her bets on Sean Connery, although she admitted to never watching any of the Bond movies in full.

This, along with her many other talents and life achievements were undercut by her wistful dismissal of it all.

“One of my friends from Bethany church said to me; ‘Hey, they’re hiring colored people at Lincoln Bank, you should go and apply you’d do so well there,’ she had said to me. So I did, and I got the job.” Speights recounted with a shrug, after ushering me to take a seat.

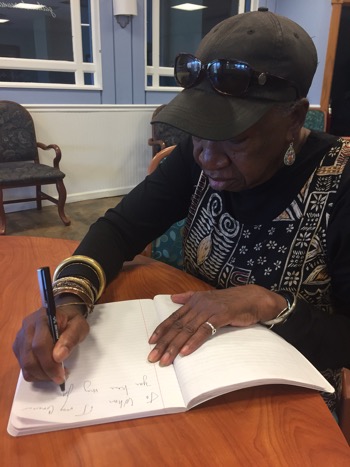

Almost immediately afterwards, she began to unearth stories of her past with a knowing grin spread across her lips. A look she said, was once famous in the city newspapers. “I was always available for photos,” she mused.

Pregnant and newly married, Speights had become a reliable source for social commentary, making her presence known at church events, rallies, and community meetings, and even at her children’s schools. All in the midst of Civil Rights upheaval which dually made its way from Montgomery, Alabama, to Syracuse, New York she said.

“ I was also a girls softball coach, a substitute teacher, and a secretary at the Dunbar center,” All of these professions, she marveled, were obtained through her persistence. A sense of value and worthiness in which her parents Katie and John Wesley, had taught her and her ten siblings. As the eldest, Speights recalls learning of the world at the young age of 4, namely the prevalence of racism and hatred that eventually lay claim to the south like a sickness.

She recounted the burden of having to teach her younger siblings the truth of it all—right there in the common room, audible to anyone in earshot. She spoke without pause, her voice reverberating with emotion from time to time.

“My father took me Downtown to work with him one day, when I still lived in Alabama” she began, her brown eyes now rimmed with a bluish halo from age, became distant. “He showed me the fountains and said ‘this fountain says white, and the other says colored.’ I was a little girl at the time, so I thought colored meant the color of the water—like Kool-Aid. I thought it spewed out different flavors, like orange or grape,” Speights said with a laugh, before becoming serious again. “But he quickly corrected me, and told me the signs were meant for people. It was from that point I realized, what it meant to be black,” she said. “But I grew up to never let it bother me. All of us, were brought up to think of ourselves as more,”

Janet Frias, 56, Speights’s eldest daughter, is a living-testament to her mother’s resilience, as she too was also taught in the ways of Katie and John Wesley.

“ My mother made it so that we were strong, and prepared for the world ahead of us, like our grandparents,” she said later that evening. Speights had pulled her number, and that of younger brother Gilbert, from a leather-binded agenda book, urging me to call—and to possibly remind them of her photos in storage. More so a joke than an actual request.

Janet’s voice continued to fill the receiver in a familiar matter-of-fact tone that resembled her mother’s.

“She reminded us that the world has changed for the better but some people hadn’t.”

Younger brother Gilbert Speights, 45, a basketball teacher at the Huntington High school, seconded her, saying that his mother is a teacher of many trades—a reference to her many jobs and professions, but also to her job as a mother for more than 60 years.

“Her patience, love, her ability to teach, and her ability to overcome,” he said, amongst other adjectives describing her bravery. “That is what makes Ms. Janice Speights remarkable,” Gilbert said. A statement that rang true in the image of Janice Speights, walking independently in the corridor.