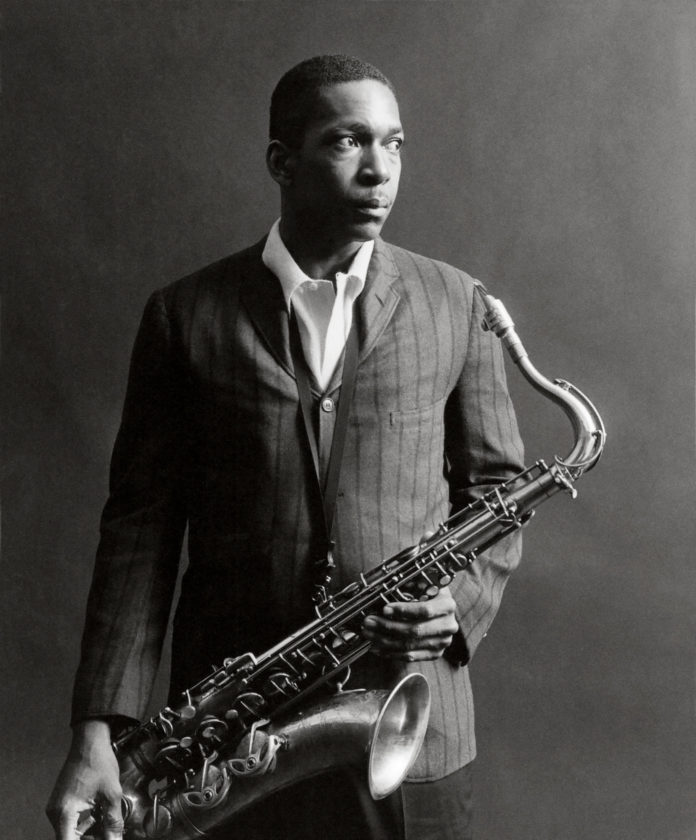

If you heard the John Coltrane Quartet live in the early-to-mid-1960s, you were at risk of having your entire understanding of performance rewired. This was a ground-shaking band, an almost physical being, bearing a promise that seemed to reach far beyond music.

The quartet’s relationship to the studio, however, was something different. In the years leading up to “A Love Supreme,” his explosive 1965 magnum opus, Coltrane produced eight albums for Impulse! Records featuring the members of his so-called classic quartet — the bassist Jimmy Garrison, the drummer Elvin Jones and the pianist McCoy Tyner — but only two of those, “Coltrane” and “Crescent,” were earnest studio efforts aimed at distilling the band’s live ethic.

But now that story needs a major footnote.

On Friday, Impulse! will announce the June 29 release of “Both Directions at Once: The Lost Album,” a full set of material recorded by the quartet on a single day in March 1963, then eventually stashed away and lost. The family of Coltrane’s first wife, Juanita Naima Coltrane, recently discovered his personal copy of the recordings, which she had saved, and brought it to the label’s attention.

There are seven tunes on this collection, a well-hewed mix that clearly suggests Coltrane had his sights on creating a full album that day. From the sound of it, this would have been an important one.

“In 1963, all these musicians are reaching some of the heights of their musical powers,” said the saxophonist Ravi Coltrane, John Coltrane’s son, who helped prepare “Both Directions at Once” for release. “On this record, you do get a sense of John with one foot in the past and one foot headed toward his future.”

That’s true — though as Mr. Coltrane was careful to point out, his father always lived in a state of transition. The poet and critic Amiri Baraka wrote in 1963 that Coltrane’s career was one of simultaneous “changes, resolutions and transmutations.” As the public came to depend on the grounding wisdom of his saxophone sound in the late 1950s and ’60s, Coltrane kept shifting and expanding it.

By the time he signed with Impulse! in 1961, he had mostly left behind the swift harmonic movement of his earlier work. He was resolutely exploring other elements: drones influenced by North African and Indian music; unbounded and jagged melodic phrasing. One of Coltrane’s earliest biographers, C.O. Simpkins, described the quartet’s shows in these years — with Mr. Jones lighting fires and Mr. Tyner splashing them with multihued harmonies — as a kind of euphoric cleanse. The quartet, he wrote, “would beat the unclean air until it begged for mercy.”

But…