In South Sudan, livestock farming doesn’t stop because of war – and veterinarians don’t stop either. Silvester Okoth from Vétérinaires Sans Frontières Germany describes work in the field

When I decided to become a vet, I never imagined it would involve seven-hour hikes across swamps, streams and rough terrain to deliver cold boxes full of animal vaccines.

I’m in South Sudan. A two-hour flight from the capital Juba, where the sky meets the ground, the shrub and grasslands are occasionally interrupted only by gunshots – either a warning to turn back or take cover.

But in places like South Sudan, where there has been conflict since 1955, animal health forms an important part of the humanitarian effort.

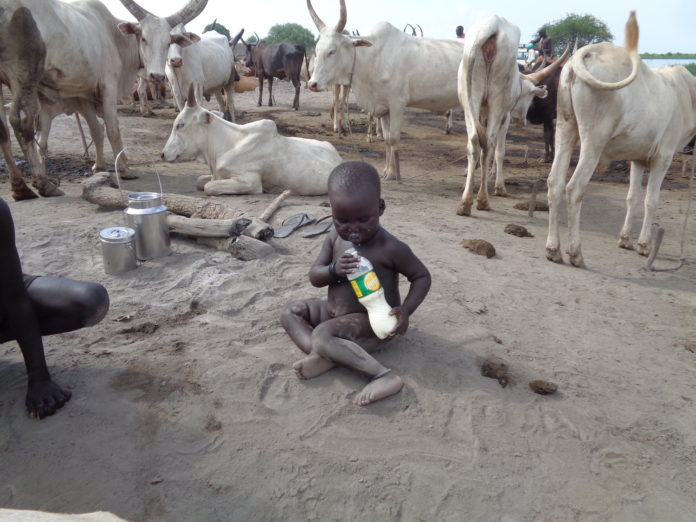

Interestingly, and fortunately, war does not entirely wipe out the livestock market, despite the fact that most pastoralists have lost their herds. In fact, in some areas where farmers are unable to grow grains, farm animals are the only source of food when everything else is scarce.

In such circumstances, it is crucial that we protect these animals as much as possible, especially because milk is a lifeline for the more than 275,000 children kept hungry here in South Sudan by war. Real improvements are only possible when relative peace can happen for a long period of time. This allows us to introduce more productive and quicker-maturing breeds.

Discover the good news that matters.

Otherwise, the best we can do is vaccinate cows, sheep and chickens against key and endemic diseases, to safeguard them for food or for sale. Doing so is not easy at all. The road network has deteriorated because of the conflict, so we have to travel via aircraft. But this still leaves us hours from the field, and in the middle of a war, planes are normally reserved for priority life-saving…