The Indian revolutionary, who coined the slogan ‘Inquilab Zindabad’, demanded that the British send a military detachment to execute him by firing squad; the Hindu nationalist promised to give up the fight for freedom if released – and kept his word.

Note: This article was first published on March 23, 2016, and is being republished today to mark Bhagat Singh’s death anniversary.

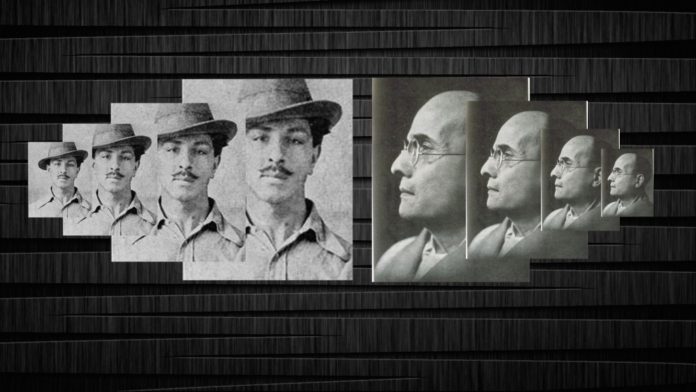

Eighty-five years ago, on March 23, 1931, Shaheed Bhagat Singh and his two comrades-in-arms, Shaheed Rajguru and Shaheed Sukhdev were hanged in Lahore by the British colonial government. At the time of his martyrdom, Bhagat Singh was barely 23 years old. Despite the fact that he had his whole life ahead of him, he refused to seek clemency from the British as some well-wishers and family members wanted him to do. In his last petition and testament, he demanded that the British be true to the charge they laid against him of waging war against the colonial state and that he be executed by firing squad and not by hanging. The document also lays out his vision for an India whose working people are free from exploitation by either British or Indian “parasites”.

At a time when the Bharatiya Janata Party national executive has decided to make nationalism its rallying cry, it is useful to compare the patriotic attitude and vision of Bhagat Singh with that of the Sangh parivar’s icon, V.D. Savarkar, author and originator of the concept of ‘Hindutva’, which the BJP swears by.

Sent to the notorious Cellular Jail in the Andamans in 1911 for his revolutionary activity, Savarkar first petitioned the British for early release within months of beginning his 50 year sentence. Then again in 1913 and several times till he was finally transferred to a mainland prison in 1921 before his final release in 1924. The burden of his petitions: let me go and I will give up the fight for independence and be loyal to the colonial government.

Savarkar’s defenders insist his promises were a tactical ploy; but his critics say they were not, and that he stayed true to his promise after leaving the Andamans by staying away from the freedom struggle and actually helping the British with his divisive theory of ‘Hindutva’, which was another form of the Muslim League’s Two Nation theory.

Reproduced below are Shaheed Bhagat Singh’s last petition and the petition V.D. Savarkar filed in 1913.

Shaheed Bhagat Singh’s Last Petition

Lahore Jail, 1931

Sir, With due respect we beg to bring to your kind notice the following:That we were sentenced to death on 7th October 1930 by a British Court, L.C.C Tribunal, constituted under the Sp. Lahore Conspiracy Case Ordinance, promulgated by the H.E. The Viceroy, the Head of the British Government of India, and that the main charge against us was that of having waged war against H.M. King George, the King of England.

The above-mentioned finding of the Court pre-supposed two things:

Firstly, that there exists a state of war between the British Nation and the Indian Nation and, secondly, that we had actually participated in that war and were therefore war prisoners.

The second pre-supposition seems to be a little bit flattering, but nevertheless it is too tempting to resist the desire of acquiescing in it.

As regards the first, we are constrained to go into some detail. Apparently there seems to be no such war as the phrase indicates.

Nevertheless, please allow us to accept the validity of the pre-supposition taking it at its face value. But in order to be correctly understood we must explain it further.

Let us declare that the state of war does exist and shall exist so long as the Indian toiling masses and the natural resources are being exploited by a handful of parasites.

They may be purely British capitalist or mixed British and Indian or even purely Indian. They may be carrying on their insidious exploitation through mixed or even on purely Indian bureaucratic apparatus. All these things make no difference.

No matter, if your government tries and succeeds in winning over the leaders of the upper strata of the Indian society through petty concessions and compromises and thereby cause a temporary demoralisation in the main body of the forces.

No matter, if once again the vanguard of the Indian movement, the Revolutionary Party, finds itself deserted in the thick of the war.

No matter if the leaders to whom personally we are much indebted for the sympathy and feelings they expressed for us, but nevertheless we cannot overlook the fact that they did become so callous as to ignore and not to make a mention in the peace negotiation of even the homeless, friendless and penniless of female workers who are alleged to be belonging to the vanguard and whom the leaders consider to be enemies of their utopian non-violent cult which has already become a thing of the past; the heroines who had ungrudgingly sacrificed or offered for sacrifice their husbands, brothers, and all that were nearest and dearest to them, including themselves, whom your government has declared to be outlaws.

No matter, it your agents stoop so low as to fabricate baseless calumnies against their spotless characters to damage their and their party’s reputation.

The war shall continue.

It may assume different shapes at different times. It may become now open, now hidden, now purely agitational, now fierce life and death struggle.

The choice of the course, whether bloody or comparatively peaceful, which it should adopt rests with you. Choose whichever you like. But that war shall be incessantly waged without taking into consideration the petty (illegible) and the meaningless ethical ideologies.

It shall be waged ever with…