News

COMMENT | It was University of California Berkeley political scientist Arend Lijphart who first described Malaysia’s political system as a “consociational democracy,” meaning that each of the respective races in Malaysia would be represented by a key political party of their choice.

Right until May 9, 2018, which will go down in history as a monumental day, Malays had primarily believed that Umno was the main vehicle of representation to channel and articulate their interest, and that MCA and MIC would do the same for the Chinese and Indians in the country respectively.

But as much as May 9 was a huge electoral victory for Pakatan Harapan, with the seismic effects continuing to be felt from Kangar to Kota Kinabalu, there has to be due regard for the previous political system, even as Pakatan Harapan tries to strike out on an independent future to free the minds and habits of Malaysians.

In the event of any conflict or issue, arising from cabinet appointments, for instance, it helps if all sides can resort to using internal party mechanisms to forge a consensus. Speaking openly and directly to the media at the first instance – while emotionally cathartic – is politically damaging to a new government.

There are five reasons why Malaysian politicians, regardless of which party in Harapan, have to be wise and savvy, not just ‘fact-smart’. The latter involves a direct engagement with the media that can prove counterproductive to what Harapan hopes to achieve, especially in the first 100 days leading up to the next five years.

First and foremost, an election can only remove the top layer of the corrupt politicians at work. But an election cannot, at one go, remove the politicians’ hidden cronies, nominees and vested family interests.

Thus, more than anything, courage to stay the course of comprehensive reforms, should be used to root out what can be analogously referred to as the ‘deep state’, rather than to speak to the open media, let alone to tweet it, as President Donald Trump is inclined to do in the United States.

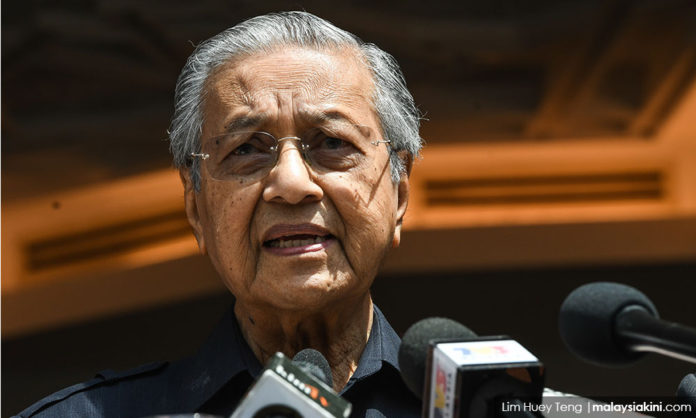

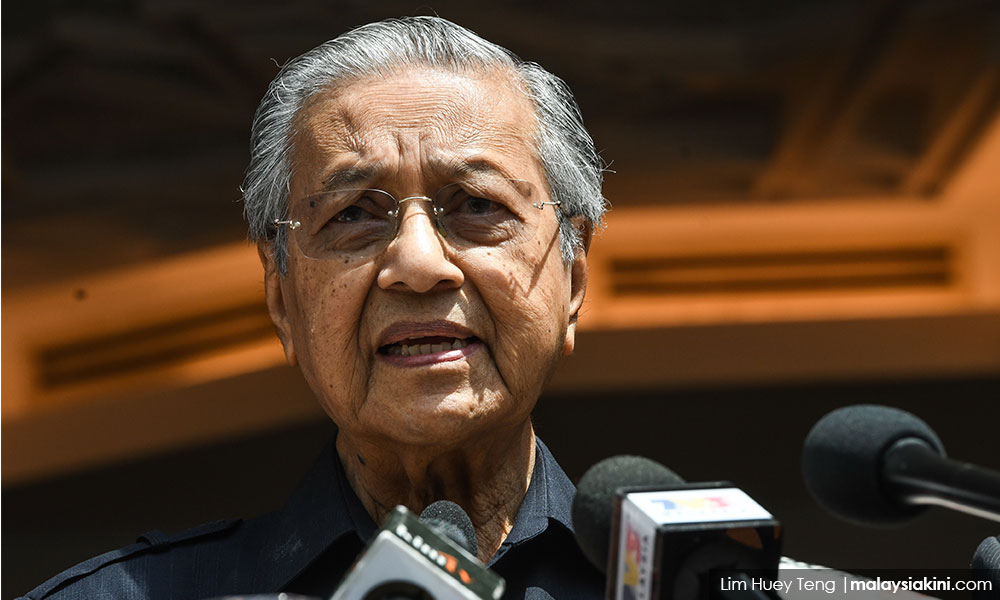

In politics, no news is good news. This period of calm can be used as a strategic platform to terminate the ‘termites’ that had been gnawing of the foundation of the state – which is the expertise of Dr Mahathir Mohamad by virtue of his extensive experience and previous track record.

Secondly, the whole point of an election is not merely to usher in the new only but to understand what has previously worked. And, if the latter has proven to be the case, there is no need to challenge it wholesale, in order to retain some semblance of stability to ensure the next phase of reforms.

For example, it defeats the purpose of reform if every single move by Mahathir is seen through the prism of ‘authoritarianism’. Doing so not only allow one to be entrapped by the past but to allow the past to be the script of the future.

Take the response of PKR Subang MP Wong Chen, for example. While he is a good colleague of mine who worked tirelessly in this monumental journey, Wong’s blanket defence of Rafizi Ramli – that any failure to critique Mahathir now will lead to a return to the iron rule of Najib – is too simplistic and falls into the realm of confirmation bias, i.e., the tendency to interpret new events as confirmation of one’s existing beliefs.

Well, to be fair to Mahathir, his problem is not criticism. In any Harapan presidential council, he gets his fair share of sound bites from everyone across the spectrum. But Mahathir rejoices in parrying these criticisms too, which is why he has earned the respect of PKR, DAP and Amanah together with the rest of Bersatu.

Democraty in Harapan alive and well

Democratic criticism is alive and well in…